The Belief in Being Belief-Free

You’ve heard it. You may have even said it — casually, perhaps even proudly, in a conversation meant to display how clean and rational your worldview is:

“I don’t believe anything. I follow evidence.”

“I only trust facts. Belief is for people who can’t think.”

This has become the philosophical version of “I’m just being honest” — a badge of honour worn by those who think they’ve transcended tribal bias, wishful thinking, and magical narratives. It’s the modern intellectual’s equivalent of flexing in the mirror and calling it humility.

We’ve entered a peculiar era — one where denying belief is the new religion. One where the phrase “I don’t believe in anything” isn’t met with concern or confusion, but applause. It’s become a kind of ontological keto diet: cut out all the carbs (faith, metaphysics, soul), and claim peak cognitive health.

But here's the kicker: the very statement “I don’t believe” is itself a belief. It assumes that belief is a thing one can shed like an old coat — that it’s optional, even avoidable — as though humans come into the world as blank slates who just happen to install ‘logic’ before they catch the ‘belief’ virus.

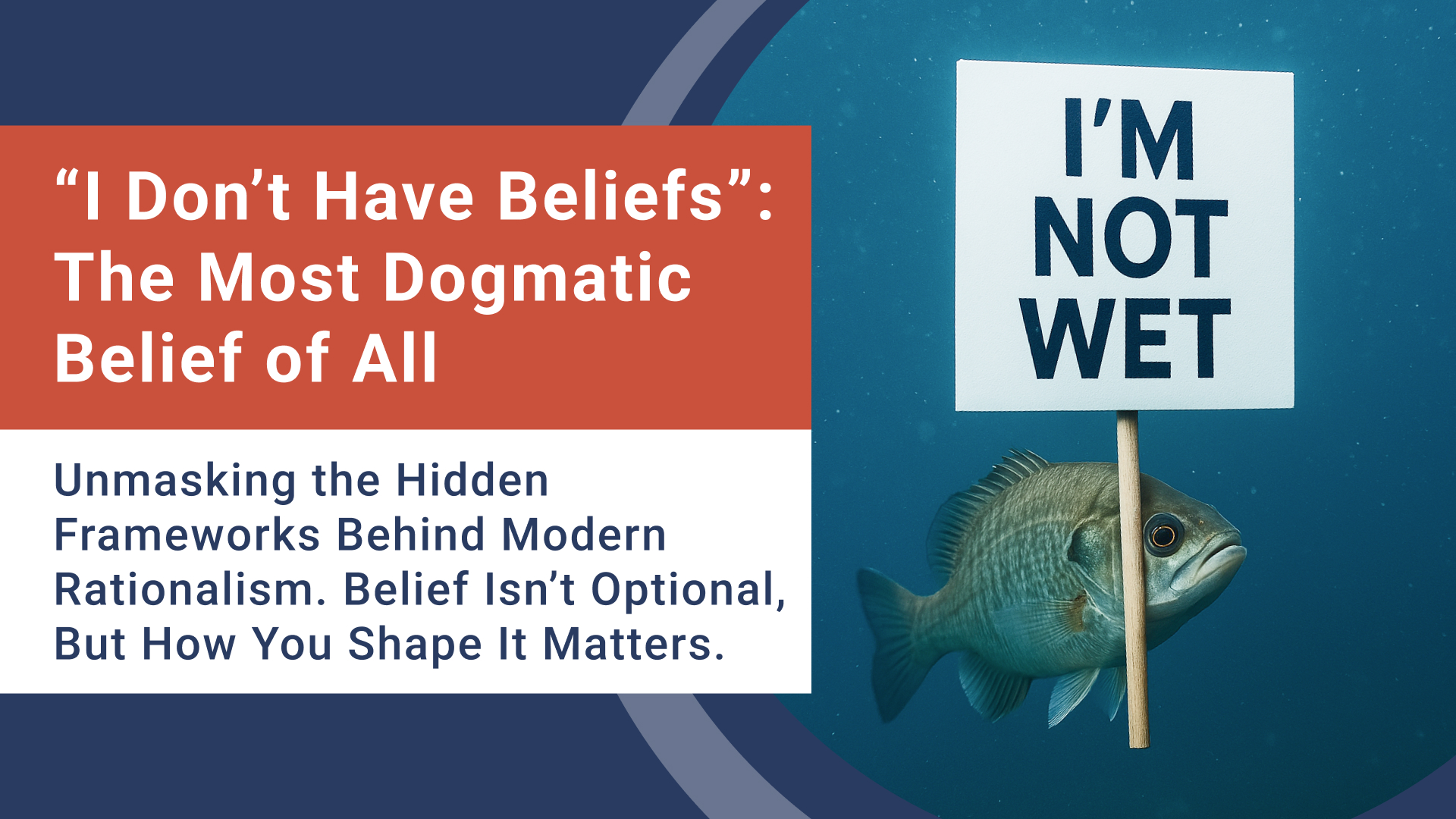

Let me offer a visual: imagine someone standing on a raft in the ocean, confidently declaring, “I’m not floating — I’m just here.”

They don’t see the water. They don’t acknowledge the raft. But without both, they’d sink instantly.

That’s what it’s like to claim belieflessness. You’re not standing on solid ground — you’re floating on layers of invisible assumptions, conceptual inheritance, cultural scaffolding, and semantic illusions. You just don’t realise it.

And in many cases, you don’t want to. Because once you admit you’re operating on beliefs, the game changes. You’re no longer exempt from reflection, from accountability, or from the slow, uncomfortable task of examining your epistemic inheritance.

But examine it we must. Because denying belief doesn’t make it disappear — it just makes you dangerous to yourself and others. Like someone who insists their car has no engine because they’ve decided to rename it “mobility hardware.”

In this article, we’ll peel back the illusion — gently in some places, sharply in others. We’ll explore how science, atheism, secular humanism, and even the most “rational” postures are built on belief, not in the pejorative, religious sense, but in the fundamental, axiomatic sense.

We’ll show why belief is NOT your enemy — and why denying it might be the most dangerous belief of all.

Belief: Not Just for the Superstitious

Let’s clear something up — the word belief didn’t fall from the sky to torment rationalists. It wasn’t invented by televangelists or medieval monks with wine-stained fingers and power issues. The term belief comes from Old English geleafa, which is related to lief, meaning “dear” or “beloved.” To believe, originally, was to hold something close—not blindly, but intimately. A belief wasn’t just a thought. It was a relational commitment.

It’s tragic, really, how far the word has fallen. Today, “belief” is treated like an intellectual contaminant — something respectable thinkers are supposed to sanitise themselves from. Like bacteria on a lab coat, it's only ever mentioned in the context of getting rid of it.

Say “I believe” in a modern discussion, and watch the temperature drop. It’s as if you admitted to seeing ghosts. Suddenly, you’re lumped in with flat-earthers, anti-vaxxers, and that uncle who thinks Elvis is alive and running a bakery in Uruguay.

But this isn’t just a linguistic misunderstanding — it’s a cultural pathology. The modern mind has been trained to associate belief with irrationality, naivety, or superstition, as if believing automatically means abandoning thought. Yet nothing could be more ironic. Because every rational process starts with belief.

Think about it: even the belief that “beliefs are dangerous”... is a belief.

Belief is the soil from which both superstition and science grow. The problem isn’t belief — the problem is unexamined, unearned, or unrestrained or as I often say inauthentic belief.

Let’s use a simple analogy: if belief were a tool, it would be a knife. Yes, you can cut yourself. Yes, you can use it to cause harm. But that doesn’t mean the knife is evil. It likely means you’re either careless or malicious. Or, more often, you’re simply unaware you’re holding it at all.

In truth, everyone believes. The only question is:

Do you know what you believe?

Do you know why you believe it?

And do you have the courage to hold those beliefs up to the light without flinching?

The tragedy of modernity isn’t that people believe — it’s that they believe they don’t believe, and therefore stop examining the foundation they’re standing on.

A person who mocks belief while depending on their own unacknowledged assumptions is not “more rational” — they’re just less self-aware.

And that, my friend, is the real superstition.

Science: The Most Elegant Belief System Ever Designed

Science. The crown jewel of modern civilisation. The sacred cow of the 21st century. The institution whose authority is so total, so absolute, that to even question its foundations in public is to risk being branded a heretic — or worse, a “non-scientific thinker.” You may as well confess to believing the moon is made of cheese.

But here’s the twist: science itself is built entirely on belief.

Now wait. Breathe. Don’t throw your Bunsen burner at me. Let’s define our terms.

When I say science is a belief system, I don’t mean it’s “just another religion.” It isn’t. It doesn’t baptise your soul or promise eternal paradise for reciting the laws of thermodynamics. But it is, nonetheless, a worldview built on axioms — and those axioms, or foundational truths, are unprovable within the system itself and those axioms, or foundational truths, are accepted and require no further proof or justification as first principles.

Let’s list a few:

That the universe is intelligible.

That nature follows consistent laws.

That cause precedes effect.

That observation yields insight into reality.

That mathematics can model the physical world.

That human senses and instruments can be trusted (at least probabilistically).

That what cannot be measured can be ignored.

None of these are scientific conclusions. They are epistemic preconditions. Science begins by believing these things are true, and then proceeds to test everything else against them.

This doesn’t make science weak. It makes it honest — if we’re honest about it. What’s dishonest is the performative smugness of those who pretend that science floats above belief, untethered to human assumptions. That it is pure, clean, stainless steel reason — untouched by bias, history, or metaphysical commitments.

It’s not. It’s the most elegant belief system ever designed. Precise, self-correcting, methodical — yes. But a belief system nonetheless.

Let me put it another way: science is like a cathedral of glass. Transparent, structured, awe-inspiring — but still built on a foundation. And if you dig under the glass floor, you’ll find the same thing you find under every system of thought: belief. Thoughtful belief, perhaps, but belief all the same.

The tragedy is that some people spend their lives working in the cathedral — studying its structure, admiring its symmetry — yet never once look down. They pretend the foundation isn’t there because it’s not labelled with a Latin name and published in Nature.

And let’s be clear: this isn’t a case against science. Quite the opposite. It’s a call to respect it more, not less. Because the most powerful tools are those whose limits we understand, not those we mistake for absolutes.

So the next time someone says, “Science isn’t based on belief,” ask them this:

“Do you believe that?”

Watch the silence that follows.

It’s not evidence they’re missing.

It’s awareness.

Atheism and the Great Epistemic Cover-Up

Now we descend into the sacred sanctuary of atheism — the default operating system of many modern intellectuals. Not a religion, they say. Just the absence of belief. A blank space where gods used to live, now replaced with reason, evidence, and YouTube debates.

“I don’t believe in God. I simply lack belief.”

This has become the atheist’s philosophical get-out-of-jail-free card. Elegant, minimal, non-committal. Like claiming you don’t eat sugar while spooning agave syrup into your third ‘clean’ smoothie.

Let’s break this down.

To lack belief in God is not a position of emptiness — it is a position of replacement. It’s not a vacuum, it’s a refilled container. Theistic claims have been rejected, yes — but something else has taken their place. And often, that “something else” is a complex latticework of beliefs, carefully curated to appear belief-free.

For example, many modern atheists (especially of the loud, militant, TED Talk variety) believe the following:

That the material world is all that exists.

That human consciousness is reducible to brain chemistry.

That morality can be explained via evolution, social contracts, or utility.

That purpose is something we invent, not discover.

That metaphysical or spiritual claims are meaningless unless they are falsifiable.

That if something isn’t measurable, it isn’t real (or worse, isn’t relevant).

Now pause. None of these are proven. They’re not facts. Their beliefs. They form a coherent worldview — one grounded in naturalism, physicalism, humanism, and a good dose of metaphysical stoicism. But they are still, at their root, assumptive frameworks — starting points, not conclusions.

To deny this is not humility. It’s a kind of epistemic cosplay — dressing up your beliefs in lab coats and calling them absent.

Here’s a metaphor to bring it home.

Imagine a man standing inside a cathedral — the vaulted ceilings still echoing with centuries of devotion, stained glass windows casting fractured light across stone floors. But instead of monks or hymns, he’s surrounded by TED Talks, neurology diagrams, and physics equations projected onto the altar. He folds his arms confidently and says, “I don’t worship anything. I just follow reason.”

But the stained glass still reflects his own face — because though the icons have changed, the structure of worship remains. The rituals are different, but the reverence is the same. The incense has been replaced with intellectual pride. The chants with peer-reviewed citations. He didn’t leave the cathedral. He just changed the hymns, swapped out the saints for scientists, the scripture for academic consensus, the divine mystery for metaphysical certainty masked as absence.

He still believes — in method, in empiricism, in materialism. He still makes meaning. Still bows to assumptions. But because he no longer calls it belief, he thinks he has none.

That’s not absence. That’s rebranding.

Atheism isn’t void. It’s a position. A rejection of one kind of metaphysics in favour of another, often without naming it as such.

And look, this isn’t about attacking atheism. One can be an atheist and still engage deeply with meaning, ethics, and even wonder. But to deny that atheism is also a belief-laden worldview is to play a semantic game of hide-and-seek — one where the mind hides from itself and calls it intelligence.

We call that a shadow — a structure that refuses to look at its own source.

You are free to be an atheist. You are free to reject every god ever named. But you are not free from belief. No one is. The only difference is whether your beliefs are transparent and authentic, or cloaked in the self-flattering illusion of neutrality.

So when someone says “I just lack belief,” ask them:

“What do you believe instead?”

The conversation will either begin or, more likely, end right there.

But either way, you’ll be closer to the truth.

Religious Belief: Sacred Words, Unread Lives

If atheism often disguises belief as absence, many expressions of religious belief disguise absence as belief. It’s one thing to be secular and claim neutrality. It’s another to wrap yourself in the language of faith, quote sacred texts selectively, or swear allegiance to a religion — yet never engage with it deeply, consistently, or even once in your life.

Let’s not pretend this is rare. Across the world, countless people identify with a religion they’ve never studied. They believe in a scripture they’ve never read. They claim reverence for words they’ve never truly encountered. They may defend their religion fervently, even aggressively — but when asked if they’ve read their own so-called sacred text from beginning to end, the answer is often silence.

Not studied it with linguistic depth or historical context.

Not wrestled with its contradictions, poetry, or jurisprudence.

Not even read it once.

And yet, they declare it sacred.

This is the core of ontological inauthenticity — the misalignment between what we claim to believe and what we’re actually willing to explore, confront, or live by. To call something sacred but not worthy of your time, attention, or comprehension isn’t reverence. It’s a hollow theatre. It is the religious equivalent of quoting a philosopher you’ve never read or waving a flag for a constitution you’ve never opened.

Many who call themselves believers don’t believe in God as much as they believe in belonging to family, culture, and identity. Religion becomes a kind of symbolic membership. It’s inherited like a surname: accepted proudly, defended instinctively, but rarely questioned, studied, or actually understood.

And yet when that shallow, second-hand “belief” is challenged — even gently — it often triggers outrage, moral panic, or even violence. But what, exactly, is being defended? A prophet never studied? A scripture never read? A doctrine never grasped? It’s not God being protected — it’s ego, image, and the illusion of certainty.

This is why fragile beliefs become aggressive. Because what cannot withstand scrutiny must instead be guarded by force, indignation, or shame. And the more unexamined the faith, the more threatened it feels by inquiry.

This is not an argument against religion. It is a call to elevate it. To treat belief as something worthy of your mind, not just your allegiance. A sacred text deserves more than reverence — it deserves reading, reflection, challenge, and response. If you claim it as your moral compass, read the map. If you say it defines your life, examine its depth. If it’s truly sacred, it should be sacred enough to engage, not just defend.

This is the difference between ontological authenticity and existential cosplay. An unexamined belief isn’t a belief — it’s a performance. A ritual. An echo. When you’ve never read what you call holy, what exactly are you holding sacred? Your comfort? Your label? Your nostalgia?

You are free to believe. You are free to hold sacred what others question. But if you’ve never even engaged with the source of your belief — directly, personally, with honesty and courage — then you don’t really believe. You believe that you believe. And that, ironically, may be the most dangerous illusion of all.

Because the Divine—whatever form you believe it takes—is not flattered by laziness. And truth, if it is truth, never fears being read.

The Ontology of Belief: Anatomy, Mechanics, and Topology

If belief is so foundational to how we exist, make meaning, speak, and perform, then we must go beyond its cultural caricatures and psychological functions. We must study belief ontologically, not just what it is, but how it is, where it is, and what it does within the human being.

To do this, we draw upon the Ontological Triad Schema — your philosophical toolset for mapping phenomena across three domains:

Anatomy — What something is made of

Mechanics — How it functions and behaves in time and context

Topology — Where it lives in the human being and how it interacts with other domains

Let’s now apply this schema to Belief, with fresh distinctions that expand its depth and re-integrate it with the prior conversation around Authenticity, Metacontent, and Sense-Making.

1. The Anatomy of Belief — What Belief Is

At its core, belief is not merely cognitive assent (“I think X is true”) — it is a relational stance toward reality. It is the ontological glue that binds perception to meaning, and knowledge to action.

A belief is a compound phenomenon made of the following constituents:

Orientation – A directional leaning: toward truth, trust, coherence, or fear

Conviction – A degree of subjective certainty (emotionally or intellectually)

Assumptive Force – The implicit ‘givenness’ it brings into perception

Commitment – A behavioural or ethical stance that flows from the belief

Semantic Form – A linguistic or symbolic expression of the belief (spoken or unspoken)

Affective Charge – The emotional weight tied to the belief, shaping reactivity and identity

Beliefs are not static. They are living structures, and they influence everything from what we notice to how we argue, from what we fear to what we hope for.

Belief, then, is not a “statement you agree with.”

It is a constellation — part thought, part orientation, part embodied trust.

2. The Mechanics of Belief — How It Moves and Functions

Beliefs function as epistemic filters and motivational engines. Their mechanics include:

Selective Perception – Beliefs filter what data we notice or ignore

Sense-Making Initiation – They give coherence to otherwise neutral or chaotic input

Emotional Framing – Beliefs colour how we feel about events, people, or facts

Action Guidance – Beliefs dictate what seems worth doing, avoiding, defending, or pursuing

Relational Signalling – They operate as social badges or boundary markers (e.g., tribal, ideological, or moral affiliation)

But beliefs don’t just filter reality — they also self-perpetuate. Once formed, a belief:

Becomes a lens that resists contradiction

Seeks reinforcement via selective evidence

Pushes contradictory information into dissonance or shadow

Becomes tied to identity and then defends it as if it were selfhood itself

This is why changing beliefs isn’t simply an intellectual act — it’s an ontological rupture. It is a reconfiguration of what feels real, what feels safe, and who I am.

In practice, beliefs move through cognitive hierarchies:

From raw intuition or Initial Insight

Into operational mental models

And eventually down into tacit values and automatic responses.

Thus, beliefs sit upstream from personality, opinion, identity, and action — meaning they silently shape how we behave, how we present ourselves, how we see ourselves, and what we consider true or acceptable long before we articulate or even notice them.

3. The Topology of Belief — The Structural Interplay of Belief's Constituent Parts

If anatomy tells us what belief is made of, then topology reveals how those parts interact, where they live, and what tensions or alignments emerge between them.

Belief is not a flat statement like “I believe X.” It is a multi-dimensional field shaped by the interrelation of several ontological components. Together, these components create a dynamic topology — a shifting psychological and existential landscape that determines how belief shows up, solidifies, distorts, or evolves.

Let’s revisit the key constituent parts of belief:

Orientation — A directional leaning toward coherence, fear, hope, truth, etc.

Conviction — The felt degree of certainty or trust in the belief

Assumptive Force — The unconscious ‘givenness’ of the belief — how it frames perception

Commitment — The behavioural, ethical, or existential stance that emerges from the belief

Semantic Form — The linguistic or symbolic container the belief takes

Affective Charge — The emotional weight or reactivity embedded in the belief

Each of these components lives in different dimensions of the human system — and their alignment or misalignment defines the integrity and influence of a belief.

Topological Dynamics: Examples of How These Parts Interact

To explore the topological dynamics of belief, here are a few key relational tensions between its constituent parts. These are not exhaustive, but represent illustrative patterns where misalignment often leads to distortion, fragmentation, or performativity.

1. Orientation vs Commitment

When a person may be oriented toward compassion, but their lived commitment may be to safety, self-protection, or compliance, it creates ontological friction — a belief that feels good internally but produces inauthentic action.

This is where people say, “I believe in kindness,” but behave in chronic defensiveness. The orientation is aspirational, but the commitment is inherited or unconscious.

2. Conviction vs Affective Charge

You might intellectually hold a belief with low conviction (“I think honesty is important”), but the emotional charge tied to that belief could be explosive — due to betrayal, trauma, or family history.

This results in beliefs that are triggered, not lived. You “believe” in something, but it owns you instead of guiding you.

3. Assumptive Force vs Semantic Form

A belief may be held implicitly (“The world is dangerous”) but never articulated. The semantic form is vague or missing — but the assumptive force is active. This produces invisible beliefs: they structure perception but evade scrutiny.

These are the beliefs that say, “It’s just common sense” or “Everyone knows…” — without ever being said aloud.

4. Semantic Form vs Orientation

Sometimes a person verbally espouses a belief (“I believe in equality”), but their orientation points elsewhere (toward control, superiority, insecurity). The words don’t match the embodied direction.

This produces performative beliefs — beliefs used to manage image, not structure action.

5. Commitment vs Conviction

One can be fully committed to a belief with low conviction — not because it feels true, but because it is required by identity, tribe, ideology, or institution.

This is the topology of dogma: belief lived without doubt, curiosity, or integration. The result is rigidity without coherence.

Topological Integrity: When Belief Is Aligned

In contrast, when these parts align, belief becomes structurally coherent:

The orientation points toward a consciously chosen direction

The conviction is grounded, not inflated or feigned

The assumptive force is examined and transparent

The commitment flows from clarity, not fear or conformity

The semantic form reflects real inner coherence

The affective charge is metabolised, not repressed or explosive

Such a belief is embodied, lived, and resilient. It moves across contexts without collapsing. It can be expressed publicly or privately without fracture. It can be questioned without disintegrating.

This is what we mean by ontological integrity — a state of coherence where belief becomes a reliable compass for perception, decision-making, and self-expression, rather than a source of contradiction or self-betrayal.

Topological Dissonance: When Belief Collapses

But when these parts are in conflict, for example:

You say you believe something, but your affect betrays fear

You act with commitment but without internal conviction

You hold a high semantic clarity but low embodiment

— then your belief structure becomes topologically unstable. You experience internal conflict, relational dissonance, and performative expression that doesn’t reflect Being.

This is when belief is not a foundation, but a performance.

Not a guide, but a mask.

Not a compass, but a costume.

And when your belief has no leg to stand on, so too will your commitment, conviction and effectiveness, leaving you to bear the consequences of collapse.

Why Topology Matters

Belief is not just a content statement. Its power and authenticity lie in its internal topology. A misaligned belief may sound true but feel false. It may guide action but undermine identity. It may comfort one moment and collapse the next.

Understanding belief topologically allows you to:

Diagnose hidden sources of self-betrayal

Clarify why some beliefs feel unstable or exhausting

Distinguish between adopted beliefs and embodied ones

Refine belief not by changing “what” you believe, but by realigning how that belief is held

Because belief is not just a thought — it is a configuration of orientation, certainty, emotion, embodiment, and action. And when that configuration is fragmented, so are you.

The Nested Expression of Belief — How Belief Operates Across Cognitive and Existential Layers

While belief has a definable anatomy and a dynamic topology, its lived expression plays out through the layered architecture of human sense-making. Belief isn’t static. It lives, mutates, collapses, or coheres depending on which cognitive layer it operates within and how those layers interact.

By applying the Nested Theory of Sense-Making, we gain clarity into how beliefs originate, mutate, and become embedded across increasingly complex structures. This is not about what belief is made of — it’s about where it shows up and how it expresses itself across your inner architecture.

1. Abductive Given / Initial Insight

This is the seedbed of belief — often unconscious, emotionally coloured, and shaped by lived or inherited impressions.

A facial expression, silence, rejection, tone, or even a past wound may encode the initial belief: “I am unsafe,” “This is dangerous,” “I am not enough.”

These insights often feel self-evident, but they are shaped by emotional memory, not epistemic rigour.

→ Most reactive beliefs originate here.

2. Cognitive Map

Here, beliefs become conscious meaning structures. They are shaped by learning, reflection, and deliberate sense-making.

For example: “I believe autonomy is a moral good,” or “The universe is intelligible.”

This is where studied beliefs live — those you’ve examined, tested, and integrated.

→ Faulty cognitive maps result in distorted but confident worldviews.

3. Stories

At this level, beliefs are encoded into narratives. They become internal shorthand: “They’re just like my ex,” “It always ends this way,” “People like me don’t get second chances.”

→ These story-shaped beliefs are often unexamined but emotionally rehearsed — and they drive emotional logic.

4. Mental Models

This is where beliefs become procedural. They govern how we assume things work:

“If I express need, I’ll be abandoned.”

“Vulnerability is weakness.”

These models are not abstract — they are operational logic encoded through experience, conditioning, and repetition.

→ Most behavioural patterns are driven by beliefs at this level.

5. Perspectives

Beliefs also shape how we interpret reality — what we highlight, ignore, or project onto others.

A belief in scarcity, for instance, will skew your perspective even if the situation is abundant.

Belief at this level functions as a perceptual lens, often mistaken for neutrality.

→ Here, belief is indistinguishable from bias.

6. Domain

Beliefs are expressed through specific domains of life: parenting, leadership, love, religion, politics, and work.

The same individual may hold beliefs that are congruent in one domain and contradictory in another.

→ Domain-level beliefs guide decision-making within that sphere of life, often without cross-domain scrutiny.

7. Paradigm

Paradigms are the deeper frameworks that govern what is valid, ethical, or real within a domain.

They serve as the rules of the game — mostly invisible, yet powerfully determinant.

In a trauma-informed paradigm: “Safety is the highest good.”

In a performance paradigm: “Resilience equals worth.”

→ Paradigmatic beliefs govern systemic decisions and institutional structures and often masquerade as universal truth.

Context: The Bedrock of Belief Dynamics

Context is not a layer within the nested system — it is the bedrock on which all belief dynamics unfold.

It includes:

Time and history

Place and environment

Mood and state of being

Social audience

Cultural and historical moment

Context modulates the expression, salience, and prioritisation of belief.

You may deeply believe in patience, but find yourself snapping when exhausted and under pressure.

This doesn’t make your belief inauthentic. It makes it context-sensitive.

→ Beliefs gain or lose coherence depending on whether they remain aligned under contextual pressure.

→ Without contextual awareness, even deeply held beliefs risk collapse, hypocrisy, or superficiality.

Belief in the Being Framework

Alongside the Nested Theory, the Being Framework reveals how belief moves between internal convictions and external expression, through the Authenticity Quadrant:

Beliefs (Private Quadrant): The convictions you hold internally about reality, self, others, or the world.

Opinions (Public Quadrant): The beliefs you articulate or signal outwardly — through speech, action, or posture.

Self-Image (Internal Identity): “I’m the kind of person who believes…” — where belief fuses with identity and becomes self-perception.

Persona (External Identity): “I want to be seen as someone who believes…” — where belief becomes branding, signalling, or performance.

When belief flows congruently across these layers, it reinforces ontological integrity.

When it fractures — say, when you express opinions you don’t believe, or hold beliefs that conflict with your actions — it produces dissonance, self-deception, or image-management fatigue.

The Risk of Layer Confusion

The risk of layer confusion indicates collapse or incongruence of how the same beliefs and actions manifest across different domains of someone’s life, or when different beliefs inconsistently interplay in a particular domain for someone.

For example, a person may live from a story-layer belief (“People will always betray me”) while publicly expressing cognitive map beliefs (“I believe in trust and connection”).

This creates belief incoherence — the outward story and inner conviction are out of sync.

Alternatively, one may hold a belief within one domain (e.g. “vulnerability is strength” in spirituality) and a conflicting belief in another (e.g. “vulnerability is weakness” in business).

→ Without cross-domain reflection, this split creates compartmentalised selves.

Belief as a Layered Phenomenon

Belief is not located in a single place in the mind or psyche.

It is layered, contextual, and domain-sensitive.

To address belief responsibly is to identify not just what one believes, but where that belief lives — and whether it is coherent across the nested structures of your Being.

This is not about policing belief.

It’s about defragmenting the human experience, creating space for more substance to emerge.

Because belief, when integrated from abductive insight through narrative and model, all the way to domain and identity, becomes not just coherent, but powerful.

Axioms vs Avoidance: The Ontological Integrity of Belief and the Role of Authenticity

Not all beliefs are created equal.

And not all belief is irrational.

In fact, some beliefs are so fundamental, so structurally required for consciousness and sense-making, that they are not chosen at all — they are axiomatic. Others, however, are selected not because they are necessary or true, but because they are convenient, emotionally pleasing, or intellectually lazy.

Let’s make the distinction explicit.

1. Axiomatic Beliefs: The Foundation We Cannot Observe But Must Assume

Certain beliefs do not arise through experimentation or sensory verification. They precede such processes. They are preconditions for inquiry itself — unprovable by science because they are what make science possible in the first place.

Examples include:

That the external world exists

That time flows consistently

That logic is valid

That cause precedes effect

That our perceptions, while fallible, are not entirely deceptive

That meaning is transferable via language

These are axiomatic beliefs. You don’t hold them because of an experiment — you hold them because, without them, no experiment can be meaningful, no method can operate, no statement can be intelligible.

They are not empirical, but their structural necessity epistemically justifies them. And to discard them under the banner of scepticism is not rationalism — it’s epistemic suicide.

Holding these beliefs isn’t a sign of irrationality. It’s a sign that you are functioning — that your sense-making architecture is intact.

2. Fickle Beliefs: The Unexamined Convenience of Intellectual Laziness

Now contrast this with beliefs that fall squarely within the domain of scientific, logical, or empirical inquiry, but are accepted (or rejected) due to:

Personal comfort

Bias reinforcement

Social conformity

Intellectual fatigue

Fear of complexity

Image preservation

Here, we find beliefs such as:

“I believe what the majority of scientists say — when it suits my worldview.”

“I believe all religions are equally wrong because I’m secular.”

“I believe in my truth — because it feels right.”

“I believe X because the alternative makes me uncomfortable.”

These are not axiomatic. These are epistemic short-circuits — beliefs selected not through rigour or coherence but through emotional filtering or social mimicry. They are not foundational; they are convenient.

In the Metacontent Discourse, this is the moment where belief stops being a tool of clarity and becomes a defence mechanism.

This is not just dangerous on an individual level. When unexamined, emotionally convenient or socially reinforced, beliefs become widespread and can ripple outward — infiltrating institutions, reshaping cultural norms, and warping the very structures through which societies distribute power and define legitimacy.

Fickle beliefs scale.

And when they do, they no longer merely distort personal worldviews — they begin to sculpt the operating assumptions of entire systems: governments, media ecosystems, education models, legal frameworks, and even “scientific consensus.” At this level, beliefs aren’t just misguided — they’re weaponised.

We see this in the rise of ideologies that are immune to scrutiny yet ravenous for enforcement. In policies justified by popular sentiment rather than coherent philosophy. In entire organisations built on branding slogans that collapse under inquiry, but survive because they "feel right" or “signal the right thing.”

This is how ideological capture occurs — when a system’s authority is no longer grounded in ontological coherence or ethical reasoning, but in performative allegiance to dominant narratives, no matter how fragile, contradictory, or outdated they may be.

Over time, these narratives ossify. They become bureaucratised. Defended not through dialogue but through institutional inertia, PR machinery, and moral intimidation. We stop questioning what is true and start protecting what is familiar.

This is the root of systemic entrenchment — when power structures no longer evolve in response to truth, but instead double down on inherited beliefs that serve their preservation. At that point, epistemic laziness is no longer a personal issue — it’s a civilisational liability.

In the Metacontent Discourse, we name this for what it is: a collapse of sense-making integrity. A condition where what is repeated replaces what is real, and convenience eclipses coherence.

This is why belief — if left unexamined — can become a source of dysfunction far beyond the individual. When held authentically, belief enables clarity, coherence, and meaningful action. But when belief is held carelessly, it becomes the scaffolding for systemic confusion, coercion, and stagnation.

3. The Role of Authenticity: The Ontological Mirror

This distinction between axiomatic belief and lazy belief mirrors a deeper phenomenon — one captured elegantly in your own words:

Authenticity is how you relate to the reality of matters in life. It is the extent to which you are accurate and rigorous in perceiving what is real and what is not. It is also how sensitive and diligent you are to the validity of the knowledge you perceive. Authenticity is paramount for you to carefully consider that your conception of reality – including your beliefs and opinions – is congruent with how things are. When you are being authentic, you are compelled to express your Unique Being – what is there for you to express – while being consistent with who you say you are for others and who you say you are for yourself. It is the congruence or alignment of your self-image – who you know yourself to be – and your persona – who you choose to project to others.

A healthy relationship with authenticity indicates that you take the time to thoughtfully consider your beliefs and opinions, as the validity and accuracy of your conception of matters is important to you. You mostly experience yourself as being true to yourself and others. Others may consider you genuine, distinct and trustworthy, and that your actions are consistent with who and how you are and what you communicate.

An unhealthy relationship with authenticity indicates that there may be no solid foundation for your beliefs and opinions and how you choose to examine reality, and you are often lenient and fickle with how you express your views and the truth. You may consider yourself to be fake or an imposter and often question your own abilities. Others may consider you to be someone who lacks sincerity and often acts inconsistently with who you say you are. You are frequently uncomfortable with being yourself and being with yourself. Alternatively, you may be righteous, opinionated, biased or prejudiced, considering your ‘truth’ to be the only truth, and may be unwilling to give up being ‘right’.

Reference: Tashvir, A. (2021). BEING (p. 250). Engenesis Publications.

Here is the linchpin:

Belief, when held authentically, reflects a commitment to reality—even when that reality is inconvenient, uncertain, or disorienting.

But belief, when held inauthentically, becomes theatre. It becomes posturing, self-deception, or a coping strategy dressed up in intellectual clothing.

Let’s revisit your full distinction in this light:

A Healthy Relationship with Authenticity and Belief

You take time to consider the validity of your beliefs and opinions.

You pursue congruence between belief and reality, even if it costs you identity or certainty.

You regularly review and revise your beliefs based on a deeper understanding, not just surface agreement.

You express your beliefs with integrity, not as slogans, but as real positions backed by coherence.

You allow others to see you in progress, rather than performing certainty.

In this state, your axiomatic beliefs are respected, and your contextual beliefs are refined through study, dialogue, and discernment.

You are not rigid, nor fickle — you are epistemically agile and ontologically responsible.

An Unhealthy Relationship with Authenticity and Belief

You accept or reject beliefs casually, based on preference, not process.

You perform beliefs in public that you haven’t earned in private.

You swing between self-doubt and opinionated righteousness, depending on the room you’re in.

You collapse belief into identity and become hostile to anything that threatens your imagined self.

You confuse feeling convinced with actually understanding what you believe.

In this state, you may either become a detached sceptic who refuses all belief in the name of neutrality, or a dogmatic echo of others’ belief systems that you’ve never metabolised.

Both are expressions of a fractured relationship with authenticity, and both lead to deep dissonance in the Beliefs and Opinions quadrants of your Being.

4. Realigning Belief with Authenticity: The Practice of Ontological Integrity

To navigate belief authentically means to live this commitment:

“I do not believe because it is easy. I believe because I have traced the terrain, stood in the uncertainty, and emerged with conviction that reflects both reality and alignment.”

Authentic belief:

Is transparent

Is structured

Is examined

Is lived

And is open to refinement

It is not stubborn.

It is not smug.

It is not marketable.

It is earned.

And that — more than any credential or claim — is what makes your belief yours.

Belief and Authenticity: A Comparison Table

Meaning Requires Belief — Period

Let’s talk about meaning — that elusive, intoxicating thing we all secretly (or openly) crave. It’s the reason we write books, raise children, build businesses, fall in love, donate to causes, or stare at the stars in existential wonder.

And here’s the cold truth wrapped in velvet irony:

You can’t make meaning without belief.

None. Zero. Zilch.

Not a single drop of meaning can be conjured in a belief-free mind.

Because meaning isn’t data. It isn’t carbon, nor calcium, nor quark. You can’t weigh it on a scale, run it through a spectrometer, or distil it from lab rats and pie charts. Meaning is assignational — it is projected, woven, interpreted, and felt. And it always emerges from a position.

You may think you’re choosing meaning rationally, like selecting toppings at a frozen yogurt bar — but behind every cherry and pistachio swirl is a set of assumptions: about value, purpose, truth, beauty, good, bad, real, unreal, worthy, and unworthy.

Even the minimalist mantra “Do what works” — the tech bro’s replacement for moral philosophy — is soaked in belief:

That “working” is an acceptable metric for decision-making

That outcomes matter more than intentions

That effectiveness is somehow ethically valid

But why should what “works” matter? Why not pursue what’s beautiful, virtuous, or sublime? The very moment you start to answer that question, you’re knee-deep in value-laden waters — and values, my friend, are beliefs dressed for dinner.

Let’s try an analogy:

Imagine a person who claims to live without belief trying to create meaning. It’s like a sculptor denying the existence of stone while chipping away at a statue.

“No, no,” they insist, “I’m not shaping anything. It’s just emerging naturally from neutral observation.”

What’s actually happening? They’re using unacknowledged beliefs as tools and calling it objectivity. That’s not sculpture. That’s self-deception with artistic flair.

Here’s the thing: belief doesn’t threaten meaning — it makes meaning possible. Without belief, you don’t get purpose. You get paralysis. You get relativism soaked in nihilism, sprinkled with coping mechanisms.

And make no mistake: when people say, “Life has no objective meaning,” they’re often saying, “I believe there is no meaning.” That’s still a belief — one so totalising it becomes a lens through which all meaning must now be viewed.

The irony? Those who shout loudest about meaninglessness usually behave as though life is rich with meaning. They fight for justice, pursue truth, mourn loss, and celebrate love — all while insisting it’s meaningless.

It’s like watching someone cry at a funeral while live-tweeting, “Death is just biology.”

Their biology is clearly having a very meaningful time.

So let’s stop pretending we can separate belief from meaning like oil from water. We can’t. They are emulsified — chemically bonded. Deny belief, and you poison meaning. Deny meaning, and you’re left with survival, performance metrics, and TED Talk slogans that feel deep but cure nothing.

In truth, belief is not the enemy of reason — it’s the precondition of reason. And it is the midwife of meaning.

Own it. Don’t outsource it. Don’t outsource your existential architecture to Wikipedia, peer-reviewed nihilism, or trendy podcasts hosted by people who’ve read just enough Nietzsche to be dangerous and just enough Buddhism to sound humble. Go beyond those and use your ontological responsiveness and discernment wisely.

You are not an algorithm. You are not a meat calculator.

You are a meaning-making being.

And your beliefs — owned or disowned — are the blueprint.

Belief, Power, and the Architecture of Oppression

Here's the reality that most of us don't want to confront. Beliefs don’t just live in people. They live in systems.

And when belief becomes unexamined, convenient, or performative, it doesn’t just distort private understanding — it can be weaponised by power structures to manufacture legitimacy, suppress dissent, and perpetuate control.

This is not a conspiracy theory. It is structural reality.

Throughout history, entrenched belief systems have been used by empires, nation-states, religious institutions, political parties, and media regimes to engineer compliance and sustain systemic oppression. In these cases, belief stops being a matter of individual orientation — and becomes the operating software of institutionalised dysfunction.

In a previous article, we explored the five modes of relational and ontological force: Repression, Suppression, Oppression, Impression, and Expression.

Of these, oppression is the most structurally encoded. It operates not merely at the psychological or interpersonal level, but through systems of governance, legal frameworks, education, economic models, and cultural institutions.

Oppression is not an event. It is a machinery that operates on inauthentic belief — one of its favourite lubricants.

Because when people are taught what to believe, without the tools, courage, or permission to examine it, they become manageable. Predictable. Useful.

The most efficient kind of power is not the one that threatens you with violence.

It is the one that convinces you that compliance is truth, and dissent is insanity.

In this context, belief becomes a kind of ideological currency — traded, taxed, and sanctioned according to its alignment with institutional agendas.

Entire populations can be nudged toward docility or aggression, depending on which beliefs are fed, filtered, and framed as “truth.”

That’s not liberation. That’s epistemic enslavement with a smile and we are all already experiencing this in our daily lives on multiple levels across domains

In another foundational article, we introduced three existential archetypes:

The Elite, The Crowd, and The Leader.

Each relates to belief differently.

The Elite shape and propagate belief to serve control.

The Crowd absorbs belief passively, defending what is popular over what is true.

The Leader, by contrast, cultivates belief with ontological integrity — not for dominance or conformity, but for alignment, clarity, and transformation.

The modern world is increasingly flooded with Crowds guided by Elite-engineered beliefs — all while silencing or ridiculing those rare few who dare to be actual Leaders.

That is why belief cannot be left unexamined. It is not just about personal coherence. It is about reclaiming agency from the invisible architecture of control.

So if you want to be free—not performatively, but existentially must interrogate not only what you believe, but why that belief is convenient to the system around you.

Because belief that isn’t yours is someone else’s power over you.

For further exploration of these themes, see:

Authenticity Is Dead. And You Killed It. - The Five Modes: Repression, Suppression, Oppression, Impression, and Expression

The Silent Weight of Leadership: The Grace of Responsibility, the Illusion of Power, and the Betrayal of Conformity - The Three Existential Archetypes: The Elite, The Crowd, and The Leader

Reconciliation of Repression, Expression, and Responsiveness

Ontological Clarification: Authentic Awareness and the Belief Compass

Now let’s get serious — and specific. Up to this point, we’ve dismantled the illusion that anyone can live, think, or feel without belief. But let’s be clear: this doesn’t give you a blank cheque to believe in fairy dust, conspiracy candy, or emotional convenience.

This isn’t a permission slip to start collecting ideologies like Pokémon cards.

We draw a clear distinction between belief as an inevitable condition of being and belief as an unexamined indulgence.

Just because belief is inescapable doesn’t mean all beliefs are created equal. Some are structured. Some are sloppy. Some are born of discernment. Others are born of trauma, TikTok, or unresolved daddy issues.

And this is where Authentic Awareness enters — not as a mindfulness cliché, but as a discipline of being.

Authentic Awareness begins with the admission:

“I believe, therefore I am responsible for what I believe.”

Let that sink in. Most people never reach that point. They live like ideological squatter tenants in frameworks they didn’t build, defending mental real estate they’ve inherited without inspection.

But through my body of work, we insist on epistemic accountability. You don’t get to claim beliefs just because they feel good or align with your vibe. You must be willing to:

Trace their origin (Where did this belief come from? Was it embedded in me by my culture, my wounds, my mentors, or my memes?)

Test their structure (Does it cohere logically? Is it internally contradictory? Does it collapse under scrutiny?)

Examine their function (What do these beliefs help me avoid? What do they enable me to pursue?)

Integrate them authentically (Do I live by them, or just quote them when it’s convenient?)

We call this the Belief Compass. Not a rigid dogma, but a navigational tool that orients you toward grounded, coherent, integrity-based belief structures, without needing certainty to function.

Here’s a metaphor: if beliefs are the sails of your ship, Authentic Awareness is your hand on the rudder. You don’t control the winds of the world, but you’re damn well responsible for where you’re steering.

This is where so many otherwise brilliant minds fall short. They believe — fiercely — in science, atheism, productivity, or even love. But they’ve never mapped the metacontent behind those beliefs. They’ve never asked:

Is this belief a response to truth, or rooted in fear?

Does this belief serve my alignment, or just my comfort?

We don’t glorify belief. We refine it.

Belief becomes authentic not when it’s loud, but when it’s examined, integrated, and lived with coherence.

In fact, the most authentic belief of all is the belief that we must believe — and that how we choose to believe will shape not only our lives, but our ethics, our relationships, our work, and our legacies.

This is where belief becomes not a noun, but a verb. Not a possession, but a practice.

And the only kind of belief worth holding is the one you’re willing to carry with both hands, across storms, not just post on Instagram.

Without Authentic Awareness and ontological clarity about the belief systems we adopt, the foundations upon which our lives, organisations, institutions, and entire civilisations are built cannot be integrous — and therefore cannot be sustained.

Belief, when unconscious or inauthentic, doesn’t just distort individual perception. It seeps into systems. It calcifies into norms. It metastasises into ideologies, dogmas, and unquestioned narratives that govern everything from education to economics, governance to social justice.

And when these beliefs go unexamined at scale, they lead to collective entrenchment — a state in which dysfunction, contradiction, and performative certainty become institutionalised. At that point, we’re no longer navigating truth. We’re defending inherited frameworks, not because they serve us, but because they’re familiar. Entire societies can become epistemically paralysed — stuck in legacy worldviews while claiming to be progressive.

This is why belief must be treated not as a private abstraction, but as a public force. What we believe shapes what we normalise. What we normalise becomes what we enact. And what we enact eventually becomes the default operating system of our culture — even when it’s incoherent or corrosive.

That’s why the belief that belief doesn’t matter might be the most dangerous belief of all.

In Closing: You, Believer

Let’s bring it home.

You breathe. You speak. You suffer. You love. You fight. You make decisions with limited information, plan for futures you can’t predict, and mourn losses you can’t reverse.

Therefore, you believe.

Not because you're weak. Not because you're religious. But because you're human, and to be human is to orient oneself toward meaning in a sea of uncertainty.

Even the most hardened sceptic, hunched over a microscope and quoting Carl Sagan like gospel, believes in the value of inquiry, the reliability of memory, the coherence of language, and the capacity for progress. Even nihilists who claim life has no meaning still wake up in the morning, put on clothes (usually), and choose one coffee over another, as if something matters.

Let’s call this what it is: existential cosplay.

Pretending to live without belief is like a fish declaring it’s not wet.

You’re soaked in belief — you just don’t want to admit it because you think it makes you less rational.

But here’s the paradox: only those who recognise their beliefs can begin to become truly rational.

You can’t navigate without a compass. You can’t build without a blueprint. You can’t even speak coherently without shared assumptions about what words mean and why they matter.

Belief is not your enemy. Denial of belief is.

So what do we do?

We stop pretending. We stop shaming the word “belief” as if it’s the intellectual version of cooties.

We start examining what we believe, why we believe it, how it shapes us — and who we become because of it.

We make our beliefs transparent, coherent, and authentic — not by clinging to them desperately, but by holding them up to the light of awareness and saying:

“You don’t own me. But I take responsibility for you.”

Because that’s what grown-ups do with power.

And belief — whether you like it or not — is a form of power.

So the next time someone tells you with total confidence:

“I don’t believe in anything.”

Smile. Offer them a cup of tea.

And say:

“That sounds like a belief.”

Then watch the machinery of their worldview grind to a halt for just a moment.

And in that moment, a seed is planted — not of dogma, but of metacognitive awakening.

Because beneath all our costumes, ideologies, and podcasts, we are all — all of us — believers.

The only difference is: some of us know it.

From Belief to Metacontent: The Ontological Understructure of Meaning

It’s not enough to say “everyone believes.” That’s a starting point, not a landing.

To truly understand the architecture of belief, we must go deeper. We must ask:

What shapes the beliefs we hold?

What enables them, justifies them, sustains them?

This is the domain of the Metacontent Discourse — where we no longer analyse what is said or believed, but the epistemic and ontological structures that make certain beliefs possible, permissible, or invisible in the first place.

Metacontent governs which ideas appear coherent, which are excluded as irrational, and which remain unthinkable altogether. It is not the belief — it is the conditions of believability.

For example, the belief “Only what’s measurable matters” isn’t just a statement — it reflects a deeper materialist-secularist metacontent that privileges quantity over quality, visibility over essence, data over depth. That belief didn't fall from the sky. It was shaped by historical layers of cultural metacontent: Enlightenment rationalism, positivist science, and institutional education.

Most people have no idea their beliefs are shaped by metacontent. They operate within inherited frameworks like tenants living in a furnished apartment, mistaking the décor for their own taste.

This is where the Nested Theory of Sense-Making sharpens the lens.

Initial Insight vs Studied Beliefs: Layered Impact on Cognition

In the Nested Theory, beliefs are not monolithic. They are layered across different levels of cognitive engagement. One of the most critical distinctions here is between:

→ Initial Insight Beliefs

Quick, affective, or experiential convictions.

Formed through a flash of intuition, a cultural cue, trauma, admiration, or inherited social osmosis.

These beliefs often feel obvious, self-evident, or instinctive.

But they’re often fragile, inconsistent, or not thoroughly integrated.

They're epistemically light but emotionally sticky.

→ Studied Beliefs (Cognitive Map Beliefs)

Constructed, examined, and integrated through intentional reflection, learning, and ontological inquiry.

These exist in the deeper layers of our Cognitive Maps — the frameworks that organise how we make sense of complex realities.

They’re epistemically heavy, and when coherent, they reinforce internal congruence across all other cognitive layers.

The problem?

Most people form opinions, behaviours, and worldviews from Initial Insight Beliefs — then reinforce them through confirmation bias, echo chambers, and performance.

These lightweight beliefs eventually crystallise into distorted Mental Models — flawed but rigid structures we use to interpret everything.

So we end up with people who:

Argue for "reason" while avoiding epistemic inquiry

Speak for "truth" while never examining their filters

Claim neutrality while sitting on loaded metaphysical assumptions

To reclaim cognitive integrity, we must upgrade our beliefs from untested intuition to studied, aligned structures, integrated into our deeper maps of reality.

Belief, Being, and the Authenticity Quadrant

This is where we return to the Being Framework, and specifically to the Authenticity Quadrant — the crucible in which our beliefs and their expression reveal our ontological posture.

Let’s focus on the two quadrants most affected by belief:

Here’s the key insight:

Beliefs (private) are the soil. Opinions (public) are the fruit.

When the soil is poisoned — inherited, shallow, unexamined — the fruit will always taste like performance, not truth.

People who deny belief often project "neutral" opinions that are anything but.

They have simply transferred belief from the conscious to the unconscious, replacing religion with science-worship, philosophy with TED-talk aphorisms, spirituality with ego-signalling rationality.

In the Beliefs quadrant, they maintain an internal monologue of certainty.

In the Opinions quadrant, they broadcast it with conviction — and yet neither has passed through the fire of Authentic Awareness.

Authenticity here means:

Not just holding beliefs, but knowing you hold them.

Not just forming opinions, but tracing them to their epistemic root.

Not just saying what’s accepted, but expressing what’s real.

In Being, this is coherence.

Without it, all four quadrants become theatre. You’re no longer a being — you’re a mask with algorithms underneath.

The Integrative Act

When you bring belief into the light — through metacontent analysis, nested sense-making, and ontological responsibility — you do something rare:

You transform belief from performance into position. From reaction into embodiment. From shadow into structure.

And that is not just intellectual hygiene — that is ontological maturity.

You don’t become more certain.

You become more whole.

And from that wholeness, you begin to build a life, a voice, a path — not just rooted in belief, but in earned, integrated, aligned belief.

The kind that doesn’t need to shout to be true.

The kind that doesn’t collapse under scrutiny.

The kind that says: I know what I believe. And I know why.

Conclusion: The Responsibility of Believing

You are not a blank slate. You are not a floating brain piloting flesh with zero bias. You are a meaning-making, belief-wielding human being. And that means you have power—not the loud, performative kind that dominates conversations or flashes credentials, but the kind that silently shapes perception, decision, and culture.

Belief is not neutral. It is directional. Every belief points somewhere: toward truth or convenience, coherence or confusion, alignment or collapse. Left unexamined, belief becomes a script you perform rather than a compass you consult. You imitate, defend, and repeat narratives you’ve inherited, all while insisting you’re being “rational” or “objective.”

This is the cost of ontological inauthenticity: to live by beliefs you didn’t choose, can’t trace, and won’t examine, while claiming to be free.

So, where does that leave us?

It leaves us with responsibility. Not just to believe, but to believe consciously. To trace the origin of our beliefs, examine their architecture, and refine them into structures that are worthy of being lived by. This is the work of metacognitive maturity—not to avoid belief, but to own it with clarity, rigour, and courage.

You don’t need to believe everything. You don’t need to believe what you were told. But you do need to believe with integrity. Because whether you are raising a child, building a business, casting a vote, making art, or choosing how to act in the next moment, your beliefs are already at work.

And if the future is to be less performative, less fractured, and less manipulated by unearned narratives, then we must reclaim belief from both superstition and pseudo-neutrality. We must treat it not as a shameful admission, but as a vital human faculty that, when refined, makes everything else possible.

Believe. But do so with awareness. With structure. With intention. And with the courage to revise when the truth asks more of you than comfort does.

Because belief isn’t weakness. Denying belief is.

And authenticity isn’t a performance. It’s the discipline of owning your inner architecture—so you can live it, lead with it, and leave behind something more coherent than what you inherited.

That isn’t just maturity. It’s Being.